“Where have the women gone?”: exploring industry equality

If the design industry is to avoid “marching towards obsolescence” it must create and embrace real change, according to design leaders.

“The world is male-shaped and then adapted for women”, says design diversity organisation Kerning the Gap founder Nat Maher. Even the design industry, which is full of people who are problem solvers by vocation, has not been able to change this.

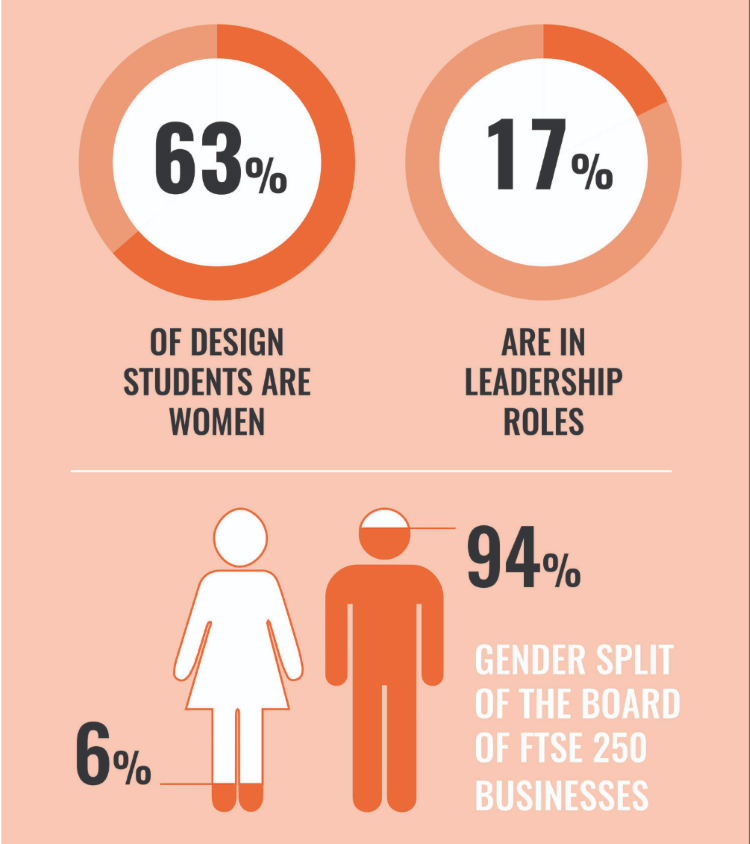

The Design Council’s 2022 Design Economy report revealed that the industry is disproportionately male, with only 23% of designers identifying as female. The figures have shifted by 1% since its first report in 2015.

There is an even larger disparity when it comes to designers in managerial positions, with men dominating 79% of them.

Most will already hear alarm bells ringing, but it gets worse. At college level in the UK, female students have consistently achieved higher grades than their male counterparts since 2010 and a huge 63% of design education students at university level are female, according to Kerning the Gap’s figures.

It begs the question: “Where have all the women gone?”, says Maher.

“Inhospitable and incompatible”

Maher identifies the early 30s as the real “crisis point” when women start to disappear from the industry. For the last decade, the average childbearing age in the UK has sat at around age 30, according to Statista.

While this offers up some explanation, Maher questions why so many of them do not re-enter the industry after having children. Her answer is that design agency environments are “fundamentally inhospitable and incompatible with family life”.

“Working 70 hours a week, pitching at the weekend, pulling all-nighters. It’s a lot of pressure”, says Maher.

So, how can the industry adapt? “By a doing a hundred different things consistently”, according to Maher, though she admits this is harder for smaller businesses with less cash in the bank and no HR department.

Pentagram partner Marina Willer is one of the few who made it to a managerial designer position. Willer puts much of her unobstructed success down to her deciding to have children slightly later in life, when she was already a creative director at Wolff Olins.

Despite taking a year off after an “extreme pregnancy” with twin boys, Willer “felt confident” coming back to work because of her professional experience, something that she realises is “much harder for junior designers”. She was also able to afford childcare due to her success.

Willer, who studied at the Royal College of Art in London for her Masters, says that many of her talented classmates “don’t seem so visible anymore” in the industry. She suspects the reason is having to prioritise family over their careers.

In a similar vein, she has noticed that “a lot of women who have taken leading positions in the industry have decided not to have children, or were not able to because of the pressure of work”. In her view, the industry needs to find ways for people to have both.

“Designers can’t just sit and wait”

One attempted solution was shared parental leave, which came into play six years ago, allowing mothers to share a portion of maternity leave and pay with their partners. Only 2% of men took up the opportunity, according to the Guardian. It also revealed that less than a third of fathers choose to take statutory two-week paid paternity leave.

Maher believes inequal pay is to blame because, in a heteronormative relationship, men generally earn around “20% more than women, even if they have equal roles”. For many couples, it makes sense for higher earner to go back to work.

Both Maher and Willer praise Scandinavia’s solution, which includes free nurseries and creche support, expressing that this should be more prevalent on the UK government’s agenda. But Scandinavia has something that the UK does not: a largely female government.

The UK government appeared negligent to women’s issues earlier this year, when it rejected a proposal for a “menopause leave”. Since menopause coincides with a “real maturing point in your career”, Maher says this could have been a “tidemark policy” and helped to combat the fallout of women across the design industry.

In the absence of government-imposed legislation, Willer says that that “designers can’t just sit and wait” for the government to act. She suggests industry leaders should accept that some people may need flexible hours when it comes to childcare and menopause.

“One thing about design is that there’s a pressure to be creative and to deliver, which is really quite specific,” says Willer, adding that “it can be painful if you’re not feeling on top of your game”.

“Lead by example”

Saying that “a brilliant designer should be able to put themselves in the shoes of anybody” does not take unconscious bias into account, says Maher. She adds that believing you can “think intuitively for all demographics” is arrogant.

Household co-founder and chief executive officer Julie Oxberry considers how having a diverse board from the studio’s conception has encouraged more women to rise through the ranks.

Oxberry came to design as her second career at age 30. She had a social sciences degree from Warwick University, had travelled across the US for eight years, eventually returning to the UK to study design at the London College of Professional Studies.

“Because I was older and had a bit of world experience, I was perhaps less worried about speaking up”, says Oxberry, though she did notice male dominance more in larger design businesses.

Household was set up in Shoreditch by five female founders and one male in 2004. Oxberry says: “It was a fantastic feeling that we made that happen and that the majority of our board and directors are still female.”

She feels there are very few female role models across the industry “particularly at senior levels”, adding that women already in these positions should “lead by example and set the bar”.

Household tries to be as hospitable as possible, while giving a platform to designers on every level, “from junior to director”, she explains. “It is important that women feel like they can speak up and don’t need to be polite.”

Willer agrees that women are often taught “not to be so comfortable, loud, confident, or visible” and that junior designers must be able to “see examples they can relate to” to believe they can climb the industry ladder.

Having more women in senior positions has the potential to create an empathy-driven ripple effect on issues like lack of support during motherhood and menopause. Household embraces hybrid working and flexi-hours and Oxberry says its diverse board helps the studio to practice a more “democratic” hiring process.

“You can’t teach someone how to be a woman”

Male-dominated senior roles ultimately mean more men doing the hiring. “We look for people who are like us and demonstrate the qualities we recognise in ourselves and so the cycle perpetuates,” says Maher.

She explains how there is a “short-sighted willingness” industry-wide, as people make small efforts to hire women for senior roles but are immediately discouraged when there are not any ready-made female creative directors.

Employers should be looking to “hire potential” says Maher, because “it is possible to train a very talented senior designer to be a design director in the space of six months”.

“You can teach leadership skills but you can’t teach someone how to be a woman”, she adds.

Studio Lutalica founder and creative director Cecilia Righini bypassed the vicious cycle by taking matters into their own hands and starting their own studio in 2020. Righini believes that, if there is no space for women and queers in the industry, designers must create some. Studio Lutalica aims to do just that by committing to hiring feminists and queers and working with ethical clients.

Righini – who identifies as non-binary – has a BA in Design and an MA in Gender Studies. From being asked to remove their pronouns (they/them) from email signatures to avoid offending clients, to being “harassed constantly” for not wearing any makeup and not wearing a bra, Righini’s limits were tested in their first few roles.

Then they joined a web development agency, which was actively looking for women and gender nonconforming people, where colleagues started to use pronouns in their email signatures so Righini would feel comfortable doing the same.

“Power is determined by the client’s money”

Since starting Studio Lutalica, Righini has found that clients are paying attention to studio demographics. “Who is your team? Who are the people in it? Are they all white? Are they all straight?”; these are just some of the questions that Righini sees cropping up on proposal forms. They feel this is a reason why the studio is doing well, as diverse teams are slowly becoming more desirable to clients.

“It’s about how clients ethically engage from their side as well”, says Maher, because “power is completely determined by the client’s money, so power belongs to them”.

In the same way, clients can help improve the structure of a designer’s work schedule to suit family life. If clients can accept that some designers might work a four-day week, avoid “demanding work to be delivered at nine o’clock on a Friday night”, and respect the fact that designers have personal lives, studios won’t need to put as much pressure on their teams, says Maher.

“Marching towards obsolesce”

“If the design industry can’t come up with solutions on how to make better environments for women to succeed in, no other industry stands a chance,” says Maher.

Non-diverse teams run the risk of producing “one-dimensional works” says Willer, while Oxberry believes it could cause some studios to “flatline”. The other side of the coin is the “richness and added value” that diversity can bring to design outputs, says Righini.

One of the most “frustrating barriers” is that people think equality has already been achieved, says Maher, describing how the subject of women’s issues attracts “bursts of cultural attention” before “the zeitgeist moves on”.

“International Women’s Day is a lever that helps crack open the conversation but we should be talking about this 365 days a year”, says Maher. She has a lot of faith in Gen-Z to “create demand from the bottom” as they are “increasingly demanding” when it comes to workplace expectations.

If studios do not foster an environment that appeals to Gen-Z, they risk “marching towards obsolescence”, Maher warns.

Banner image credit: Monkey Business Images on Shutterstock

-

Post a comment