“There’s a massive potential for design”: an Australian design guide

For the latest in our series of country guides, we turn to Australia where complex climate and social issues are influencing a new generation of designers.

In Perth, Australia, a series of public bus stops represents a personal journey for graphic designer Kevin Wilson. The redesigned signage features Aboriginal artwork, rendered in a minimalist style and simple colour palette. The interconnecting lines symbolise the younger generations who pass on stories and the new energy they carry, according to Wilson. “The way I saw the project,” the designer explains, “we were retaking the space.”

Wilson is a Wongai man, an Aboriginal group from the Goldfields region of Western Australia. Indigenous groups represent around 3% of the country’s population, but a lack of industry representation has impacted the country’s design work. Having studied at a Technical and Further Education (TAFE) institution in Perth, Wilson co-founded Nani Creative with design manager and college lecturer Leigh Wood. Together, they work on branding and strategy for projects often relating to Indigenous issues.

The studio was prompted partly by necessity. “There were no Indigenous professional graphic designers in Perth,” Wilson says, and this had led to a few problems. One of the most significant is around authenticity and sensitivity – a widely-discussed problem in the design community in the past year. In the wake of Black Lives Matter and last summer’s race protests, many companies rebranded following criticism about identities that relied on outdated and inaccurate stereotypes.

While many welcomed the overhauls, designers pointed out that long-term representation was the goal. Wilson agrees. “Young Aboriginal artists are pushing boundaries on Instagram,” he says, and this modern take on traditional culture inspires Nani’s output. The studio works to tell stories authentically but also to “bring them into a contemporary space”, he adds. “It doesn’t disrespect the other work,” Wilson says. “It carries the flame forward.”

“All about storytelling”

Aboriginal aesthetics – which are “all about storytelling”, Wilson says – fit well within a design framework. But there are also difficult stories to negotiate for the studio. One such project was an exhibition identity for Rottnest Island (Wadjemup in Aboriginal terminology), a holiday destination off the coast of Western Australia that was once home to a prison for Indigenous men and boys. Now camping sites and beach chalets co-exist with the largest known burial ground of Aboriginal people.

Wilson recalls being hesitant at the start of the project, and it was a fine line between being informative and overly gratuitous. The identity incorporates traditional symbols for rivers and lakes while a thumbprint motif is used throughout which shows how Aboriginal people “sought their own identity and ownership”, the designer says. “In the same way that every thumbprint is unique, the exhibition shares unique stories of Wadjemup and the people connected to it.”

Other design projects deal with more contemporary issues. Health problems like diabetes and STIs disproportionately affect the Aboriginal community. In light of this, Nani has been working with the Department of Health Western Australia on a series of pamphlets to better communicate these risks. The project required an illustration toolkit that would resonate with this diverse group of people, according to the design team.

Wilson draws inspiration from current sources, particularly graffiti and visuals from the West desert region. “It’s about taking an idea and stripping it to the point where it still tells the idea but my version of it,” he says. Bridging these divides is not always easy, though. “I feel like I’m in two worlds, back and forth constantly,” Wilson says, adding that one of things he’s happiest about is providing representation for younger Indigenous designers. Through Nani, he hopes that they can see that the dream of running a studio is “totally possible”.

“There’s a massive potential for design”

Wood and Wilson have run Nani for just over a year. That studio set-up is not unusual for Australia. The Design Business Council (DBC) estimates that around 85% of Australian studios employ less than five people. The leanness of these studios has created a proactive attitude among designers in the country, according to DBC co-founders Carol Mackay and Greg Branson.

The two designers previously ran a studio together but were inspired by frequent trips abroad to Europe and America, and in particular the work of the Design Business Association (DBA) in the UK and the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA) in the US. Now over a decade old, the DBC regularly produces research on the Australian design industry and offers business mentoring to studios. “The idea that design practices need to have a good solid business side to it is still relatively new,” Branson says of his native country. Mackay agrees, adding that “at the beginning, it was like selling something the studios didn’t want to buy or need.”

While design is gaining recognition in Australia, Mackay and Branson point to a few problems. One of those is a lack of government support, which is slightly ironic as “the government is a really large buyer of design”, Mackay says. There’s also a lack of management courses in education. Another is the absence of a major design industry association. There is the Design Institute of Australia but it focuses on interiors and product, while other groups have a low-level engagement, according to Mackay and Branson.

Despite all this, the pair are hopeful about design’s future in Australia. And now the council has to turn potential clients away, which is a far cry from when it was first set-up. “There are really smart people making really lovely work,” Mackay says. They highlight Victoria-based consultancy Atollon, where founders Tim Meyer and Nick Thorn blend their print and digital backgrounds. Design Week has also previously featured Sydney-based studio Heliograf, which created sushi-inspired lamps from recycled materials in an attempt to reduce ocean plastics.

Another is Gould Studio founded in Sydney, but with offices in Dubai, UAE and Jakarta, Indonesia. Founder Peter Gould set up the studio to design brands for the Islamic community. One such product is Salam Sisters, a range of culturally diverse dolls designed for Muslim children. Gould’s work points to opportunities of Australia’s design industry. “We sit on the edge of Asia’s largest Muslim population – Indonesia,” he says. “There’s a massive potential for design.”

Climate change is “front and centre” for design students

One inescapable concern for the emerging generation of Australian designers is the climate. David Mah, senior lecturer in urban design at Melbourne School of Design, says that “ecology and climate change is front and centre in the motivations” of his students. It was the inspiration for The Climate Imaginary, an online exhibition he presented for the city’s design week last month.

The exhibition was an opportunity to connect the local community with a global line-up of design practitioners, Mah explains. The goal was to tap into the interest in climate change but approach it from a different, more imaginative angle. “Sustainability is always seen as a problem-solving thing,” he says. “But there’s clearly a trend in Melbourne where young designers are realising it’s not a technical problem but a wider social political cultural problem.”

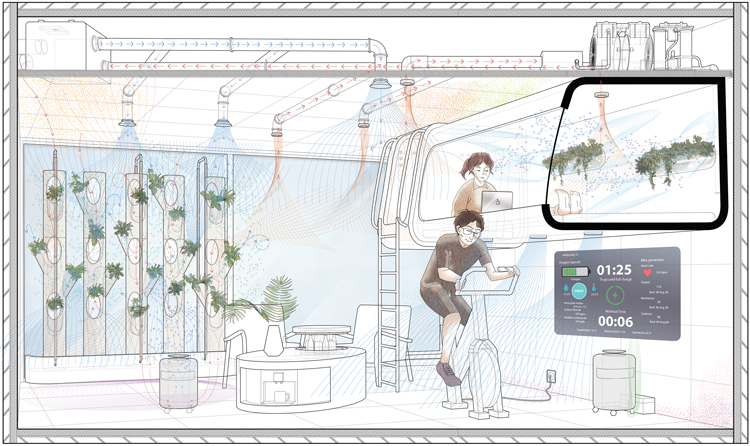

One of the featured projects is Climate House 2020, from Lydia Kallipoliti and Youngbin Shin, which proposes hacking domestic appliances to create environmental systems such as smart ventilation systems, vertical green walls and synced sleeping chambers. This took on greater relevance, Mah points out, because of all the time Australians have recently spent indoors.

First, there were the sweeping forest fires which caused toxic levels of air pollution. “Then a couple of months down the line we had to rush back in because of the lockdowns,” he says. “We’re very well acquainted with the inside of our houses.”

“There’s an understanding that boundaries are more fluid nowadays”

Melbourne’s rapidly developing population (it is growing at a faster rate than Sydney) is fertile ground for designers who are balancing this population rise with a quality of life. Mah says that the question for the exhibition was: “How can we densify but still keep those things that define the Australian lifestyle?” Vertical gardens are one solution, which means that people could still have a backyard and the all-important barbeque. Hydrosphere, a studio project set up by Mah, explores how design could ease Melbourne’s water problem, which causes both flooding and droughts.

It’s design projects that incorporate future-facing solutions and an understanding of the Australian way of living that resonate most, according to Mah. He adds that one of the highlights of the exhibition was attracting people “outside the bubble of academia” and traditional design circles. The school also created a billboard campaign for the exhibition as a way to engage with the wider public.

How do these complex issues of climate influence the designers that Mah teaches? Among his students, there’s a willingness for a more interdisciplinary approach, from architecture to ecological design. “There’s an understanding that boundaries are more fluid nowadays,” he adds.

Mah also believes that Australian design students have a strong understanding of their place in the world. When it comes to expertise about local ecologies, he says “they come to studios with that knowledge loaded up”. While it’s tempting to say that this has been prompted by climate change or the headline-grabbing wildfires, a changeable landscape has always been part of Australian culture, according to Mah. “There’s a strong awareness in Australian students to invest in the place they’re going to be working.”

-

Post a comment