“I felt responsibility to be the voice of my people”: Iranian diaspora designers pledge support

As protests continue with an increasingly strict internet shutdown, designers around the world share messages of solidarity with the women of Iran.

On 16 September a 22-year-old Kurdish woman, Mahsa (Jina) Amini, died in hospital after being detained by Iran’s ‘morality police’ for wearing her hijab too loosely three days earlier. In the wake of her death, widely believed to have been caused by being beaten heavily in custody, a protest movement has grown across Iran and around the world, led by women.

Almost a month later, the protests are persisting despite the highly punitive reaction from the government. Women of all ages are burning their compulsory hijabs and defiantly going out in public without them, and they are cutting their hair – an action traditional to mourning in Iranian culture – to commemorate those killed in the protests, estimated as numbering more than 201 by Norway-based non-profit Iran Human Rights.

Meanwhile, as those in Iran face almost near-total internet shutdown, people around the world have stepped in to speak for those who have been silenced. Designers have responded by creating protest imagery and sharing it on social media.

Roshi Rouzbehani, an Iranian illustrator now living in the UK, explains how she wanted to use her work “to show the world what is happening in Iran”. Following the internet shutdown, she says, “I felt the responsibility to be the voice of my people who are protesting against the government and fighting for freedom.”

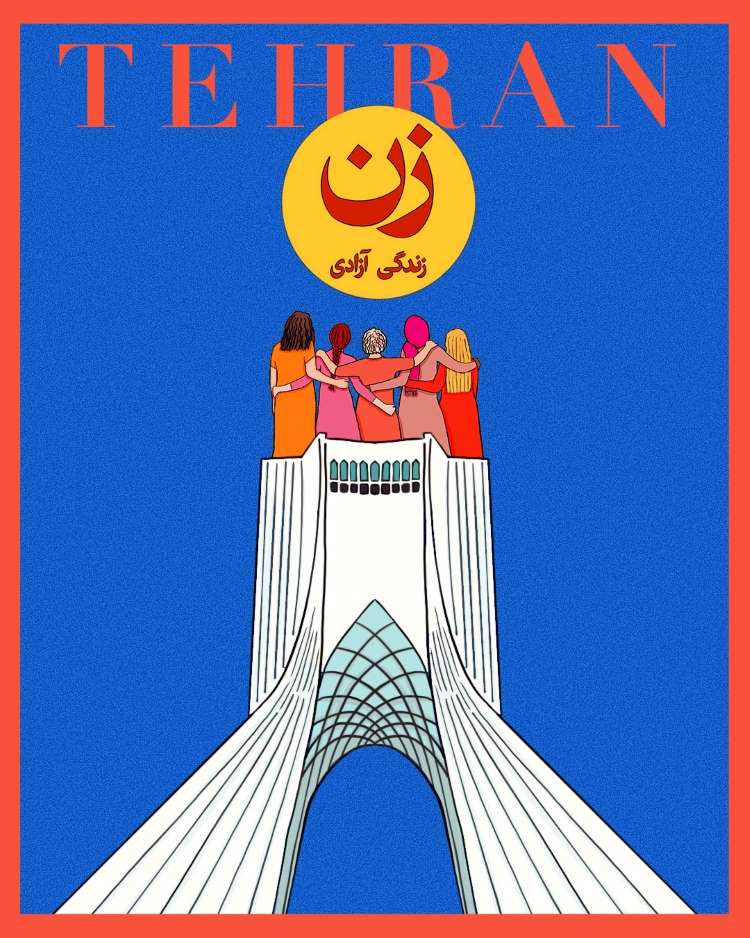

Like many of the images created for the protests, hers use the colours of the Iranian flag: green, white and red, and feature symbols of peace such as the dove, or recognisable landmarks such as the Azadi or “Freedom” Tower in Tehran.

But dominating many of the images are the colours red and black. Red, Rouzbehani explains is “to represent the resistance, anger, and also blood”, while black shows “the darkness, sadness, and mourning for Mahsa Amini and others that were killed in the protests”.

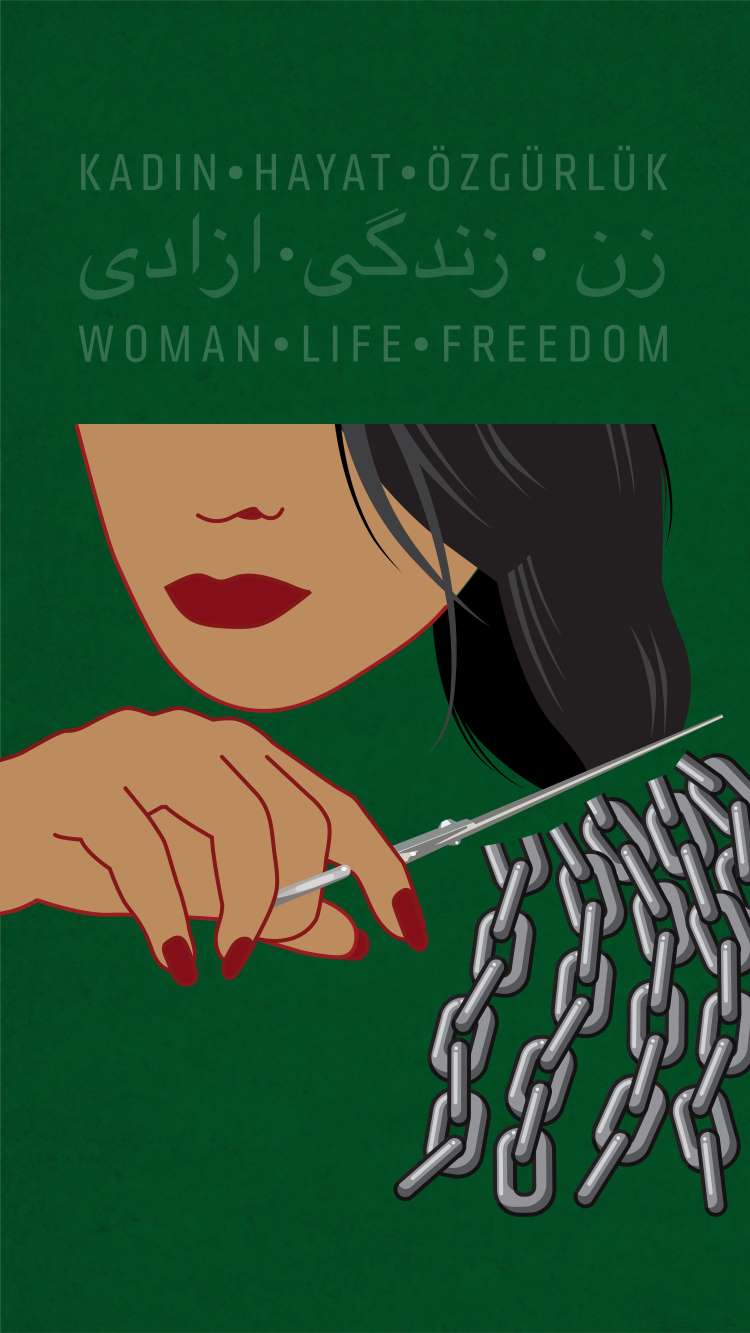

Many feature images of women, including Amini herself, to make clear that women are at the front of this movement. Symbols of femininity are asserted though red highlights – on lipstick, nails and roses.

Rouzbehani explains that she was inspired by bravery of those Iranian women who are protesting for their rights: “these defiant freedom fighters are shaping my illustration”, she says. She wants to “praise the strong women of my country that are shouting for freedom, despite the fear of getting arrested or even killed”.

The illustrations, including some commissioned for The New Yorker and the Guardian, repeat the motto used by the protestors, “Zan, Zendegi, Azadi” which translates to “Women, Life, Freedom” and is adapted from a Kurdish slogan associated with the Kurdish independence movement. It has been adopted for these protests, Rouzbehani explains, to show how women in Iran “are sick and tired of compulsive controls on their bodies, minds, and lives”.

“Being an Iranian woman is an essential part of my identity. I was born and raised in Iran and lived in Tehran until 11 years ago. So I know everything that an Iranian woman could go through and fight within everyday life living under a patriarchal dictatorship,” Rouzbehani says.

She uses visual language to transmit this knowledge to a wider audience: “I use the power of illustration to convey difficult messages in a direct way that everyone can understand with no need for translation.”

Shaqa Bovand is an Iranian typography designer based in the UK. “I’ve always been influenced by protest art, so I started using type to express my outrage about Mahsa’s death.”

Her images are simplified to black background and white type. Drawn in Procreate, the script has been arranged to fit within Instagram’s square.

While she looks back to the history of protest art, which she describes as a “time-honoured method of communication” employed by protestors to increase awareness and build networks of resistance, she describes social media platforms as the new frontier: “digital posts have taken the place of walls”.

Able to transmit messages more quickly than analogue methods, “[they] have a more significant influence on bringing about change in political situations.”

But like the other designers we spoke to, these images, after going viral online, become physical objects. Bovand has seen her typography reused on t-shirts, placards, and other protest materials, and she was surprised how it was “embraced by individuals all around the world” who printed the design on T-shirts “without knowing who created it”.

One of the designs features the message “I am not a hashtag; I am a human.” Of this message, Bovand writes, “although using hashtags can spread the news around the world, the problem is that we are talking about human life and human rights.”

Calling out to the world

Ghazal Foroutan is an Iranian graphic designer and educator now living in the US, where she teaches at Augusta University, Georgia. She has long been inspired by design activism and the idea of designing for good, and has often focused on Iranian women’s rights, looking to “shine a light on the issue[s] women face in their everyday life.”

Instead of looking to Iranian imagery for her posters, Foroutan chose to recast the image of Rosie the Riveter. Originally representative of the American women who worked in factories during World War II, this image has subsequently been used for various other women’s rights movements, Foroutan says.

As her target audience were westerners, she explains, she felt she could more successfully communicate the situation in Iran by “using a subject that they are more familiar with”.

“I illustrated our version of Rosie with her hair down and her scarf in hand. She is also showing off her tattoo that says No to Compulsory Hijab”, Foroutan explains. Rosie’s original blue apparel is kept the same, while the other colours change. The speech bubble contains “Zan, Zendegi, Azadi.”

View this post on Instagram

Foroutan used Risograph printing on colourful paper: “[The Risograph machine] was mostly used for flyers and news to be printed at high speed and in one colour so people can access it faster and cheaper”, she explains. “Alongside its eye-catching fluorescent colour palette, it made perfect sense to be used for this context.”

While the posters are downloadable, she has also created stickers in another design, making use of a format easily used by those wishing to show their solidarity.

View this post on Instagram

Like Foroutan’s work, the designs published to Instagram by Tehran- and Los Angeles-based multidisciplinary designers Studio Shizaru are addressed to those outside of Iran. The first of two images, created by its designers, Mehrdad Mzadeh and Atieh Sohrabi is captioned: “For all our non-Iranian friends: We need your solidarity & action – by spreading awareness however you can”.

But it is not only designers of Iranian heritage who have created work in support of the protests.

Professor Tevfik Fikret Uçar, chair of the Graphic Design Department at Anadolu University Fine Arts and Design in Turkey writes: “Graphic design is my way of communicating with the world”. He continues, “I expressed my reaction with the same method in war and […] during the Covid-19 epidemic, and I will continue to do this until I die”.

His images use Turkish, English and Kurdish text along with imagery of scissors, speech bubbles and flames.

View this post on Instagram

Meanwhile, data visualisation designer Federica Fragapane used her skills to communicate the reported numbers of deaths to her online audience.

She uses a motif of plaited hair to illustrate the numbers. A key within the image explains that one red strand of hair represents one death, and one white strand of hair represents the death of someone under the age of 18.

Captioning the images, she writes on the Instagram post “So many people wrote me in the last days: they’re asking us to be their voice”.

Banner image by Roshi Rouzbehani.

I’ve long admired Iranian graphics — and work created in the Persian diaspora. This is a culture which produces 80,000 graduates in calligraphy every year, where even the bazaar greengrocer knows how to form beautiful letters. Compare this to Boorish Britain, where clients routinely say: “but nobody will know the difference from Times Roman” (as if that was something to be proud of). But then graphic design has ceased to be ‘popular culture’ in the UK — around the time that it ceased to be any good at all — and is now simply about making money for shareholders. And it shows.